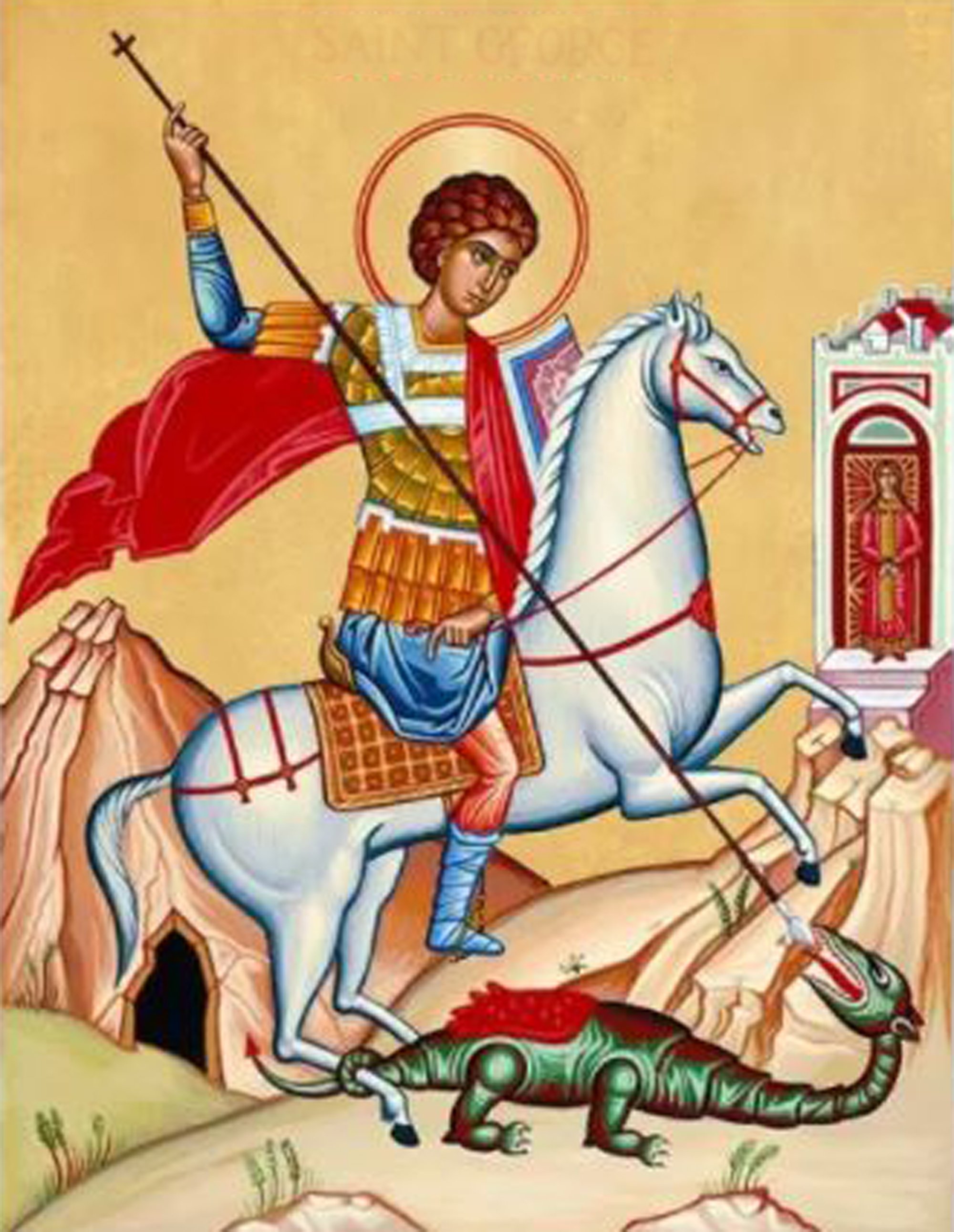

A European dragon.

Dragons have long had a place in European mythology. In medieval times those areas of the world that had not been explored were labelled on maps as ‘Here be Dragons’, ‘Here be Sea Monsters’. Chivalrous knights rescued damsels from these fire breathing creatures. One of the central figures of Christianity, Saint George, patron saint of England, is depicted slaying a dragon.

In China, by contrast, the dragon has for millennia figured prominently and positively in the culture of its people. It was the symbol of the emperor, who sat on the dragon throne. It is depicted in many forms in the imperial Ming Tombs - in sculpture, painting and on the emperor’s robes.

Dragons are the centrepiece of Chinese mythology and folklore. They possess a range of auspicious powers, especially that of controlling water, rain and floods. As China was, until this century, an agrarian society and as there can be no agriculture without water, so the people came to see the dragon as essential to their survival.

A Chinese dragon.

Most dragons are depicted as serpent-like with four legs. As with many other imaginary creatures their body parts resemble those of real life animals. The dragon is said to have the head of a crocodile, the antlers of a deer, the eyes of a demon, the ears of a cow, the neck of a snake, the belly of a clam, the scales of a carp, the claws of an eagle and the soles of a tiger. It has one hundred and seventeen scales, eighty-one of positive essence (yáng) and thirty-six of negative essence (yīn). The dragon is also closely associated with the number nine, a most auspicious number in Chinese culture. The number of scales on its body, including those that are positive and those that are negative, is divisible by nine. It is a composite of nine actual animals and there are nine sons of the dragon.

Although descriptions of dragons are legion there appear to be three main types: the lóng which lives in the sky, the hornless chī that lives in the sea and the scaly jiāo that inhabits mountainous regions. They are also classified according to the number of claws they have: the five-clawed lóng and the four-clawed and three-clawed măng lóng. The image of the five-clawed dragon, the most powerful of its kind, was reserved for the exclusive use of the emperor and was his totem - the symbol of his strength and imperial power.